It’s rolling onto 2 years since I went back independent and fully freelance, but over the 11+ years I’ve been working in design and the web, I’ve probably done around half of that as a freelancer in some capacity.

Lots of people are experiencing either redundancies or work issues at the moment and although, at the time of writing, we are in a global pandemic: now is a great time to go freelance.

In this article, I’m going to share with you some tips that have helped me make a success out of this freelancing stuff. I hope by the end that you will feel more confident about going freelance. I must point out that the advice is mainly centered around working with clients, rather than say, doing contract development work, but hopefully you’ll get some benefit if that’s you. Let’s dig in.

Freedompermalink

The “F” in Freelance stands for “Freedom”. It doesn’t really, but freedom is exactly what you get when you go freelance. This freedom for me has enabled two key things: ownership of my time and flexibility to diversify what I do.

I went back to freelancing in September 2018 after being made redundant from an agency. For at least 12 months after that, I worked in a similar role, as a freelancer: working only with clients and contracting for other agencies, along with a brief stint of guest-lecturing at the local University. Although the work was mostly the same—I even inherited a client from my old job—I worked a lot less per week. This is because I didn’t work a “normal” 9-5, but instead worked 10-4 (roughly). Those hours certainly add up.

Because the work was quite steady, I didn’t need to do much admin and business development stuff, either. This is a very valid way of going about freelance and I think it could appeal to someone who is comfortable working almost like they have a day job. The reason you work a lot less time like this as a freelancer is simple: no company bullshit. You are the boss of your own time and I promise you: you will make so much more of the time you do spend working.

Back to flexibility again, because being freelance gives you lots of that. Although I started working like the above, I knew I wasn’t going to be happy doing just client work alone. I’ve done agency stuff for so many years now that frankly, even the best client work doesn’t give me much satisfaction. I decided at the end of last year that now was the time to build an education business instead and that’s where Piccalilli, the site you are on was born.

The reason I mention this in a section about flexibility is because I’m very much transitioning into this new world. I still work for clients, but a lot less so, so I can build Piccalilli up. Granted, I’ve worked a hell of a lot more this year than last year, but the hope is by next year, I can work even less than a typical 10-4 day, thanks to the work I’m doing now.

This transition model works well too because client work pays the bills and it takes the pressure off getting lots of revenue from a business. I’m very lucky that Piccalilli is doing much better than anticipated, so I’m speeding up that transition. Because I have the flexibility as a freelancer, that is possible too. The key is that flexibility completely empowers you to work how you want to work.

Get comfortable with moneypermalink

There’s two parts to focus on here: being comfortable talking about money and being comfortable with your personal finances.

I’ll start with talking about money. You have to be comfortable talking about money with clients. In fact, when a new enquiry lands in my inbox, the first thing I do is ask them what their budget is.

So much time is wasted by being coy about money. A client needs to have a budget to hire you and let me tell you, if they refuse to tell you what that budget is, that’s a massive red flag. That refusal could be down to mistrust on their end, though—they might think you’ll use that budget to send them an over-inflated quote. I’d tackle that by saying something like this:

“In order to work out what we can achieve on this project, we really need an idea of budget. It could just be a ballpark, like £5-10k. Creating an estimate for you without this knowledge of our limitations would be a futile exercise because I have no idea what the limits of this engagement are.”

The second part on this section is your own finances. You need to know exactly how much money you need to survive every month. I have a spreadsheet that tells me how much money to take out of my business with a combination of fixed and variable costs. This helps me firstly not get stung by the tax office and secondly, informs me of how much I need to earn to survive each month.

An easy strategy to start with is try to earn your current full-time salary—especially if you are a sole trader (we’ll get to that). It’s a solid toe-dip approach into freelance.

Moving on from that approach: try to double your salary. This is because building up a buffer will make life a lot easier on a number of fronts. Firstly, it’s “get fucked” money. What I mean by that is if a client turns out to be a nightmare, you can tell them to get fucked, knowing that you have a buffer to support you. This is useful for if your client turns out to be doing very unethical worth, like working with ICE, for example. That empowerment is everything.

This leads nicely in to calculating how much you charge for your work. The first point on this is never work for free. If a client demands free spec work, bin them off and focus on other new clients instead.

I personally charge in 2 week sprints, usually, unless a project is very short, where I will charge a flat rate. For contracting work—say for an agency—only then will I charge a day rate. Sprints and day rate work normally requires a minimum commitment from them. Flat rate requires at least 50% up-front, which we’ll get more into later.

My day rate is much higher than my sprint rate. This is because day rate work tends to come with more risk, so I account for that by charging more money. It also reduces my ability to schedule efficiently, because this sort of work can drag on much longer than anticipated, so again, the client is going to pay for that disruption.

In terms of how much to charge: this comes down to knowing how much you need. Get your monthly outgoings spreadsheet, take the total and triple it. “Why the hell?!?”, they scream. We triple it because there’s a darn good chance you will experience very quiet spells, so charging a lot more for your work when you have it builds up your buffer to get you through these times. You get more ammo to tell awful clients to fuck off, and getting to that goal of doubling your full-time salary gets easier.

Get good at organising your timepermalink

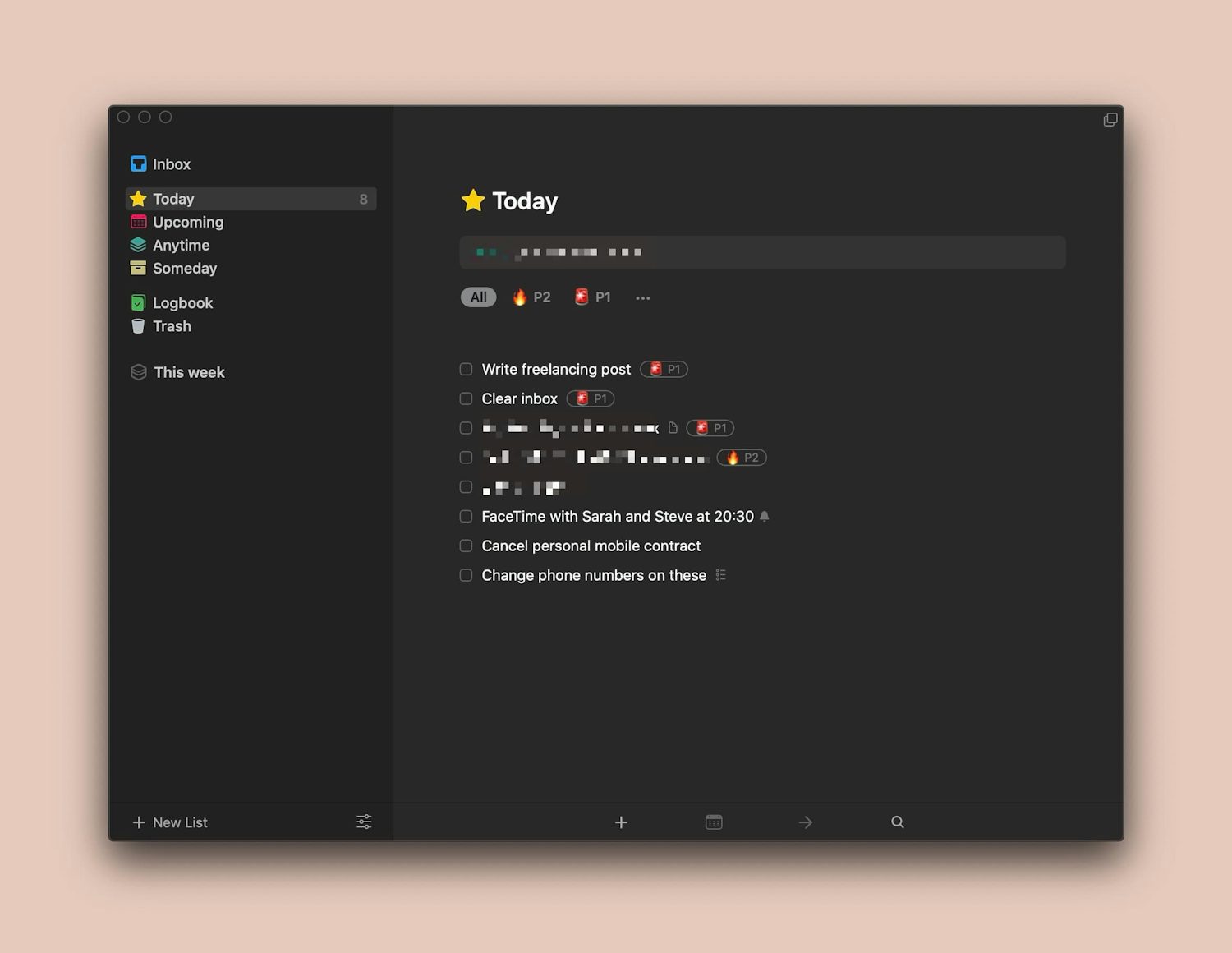

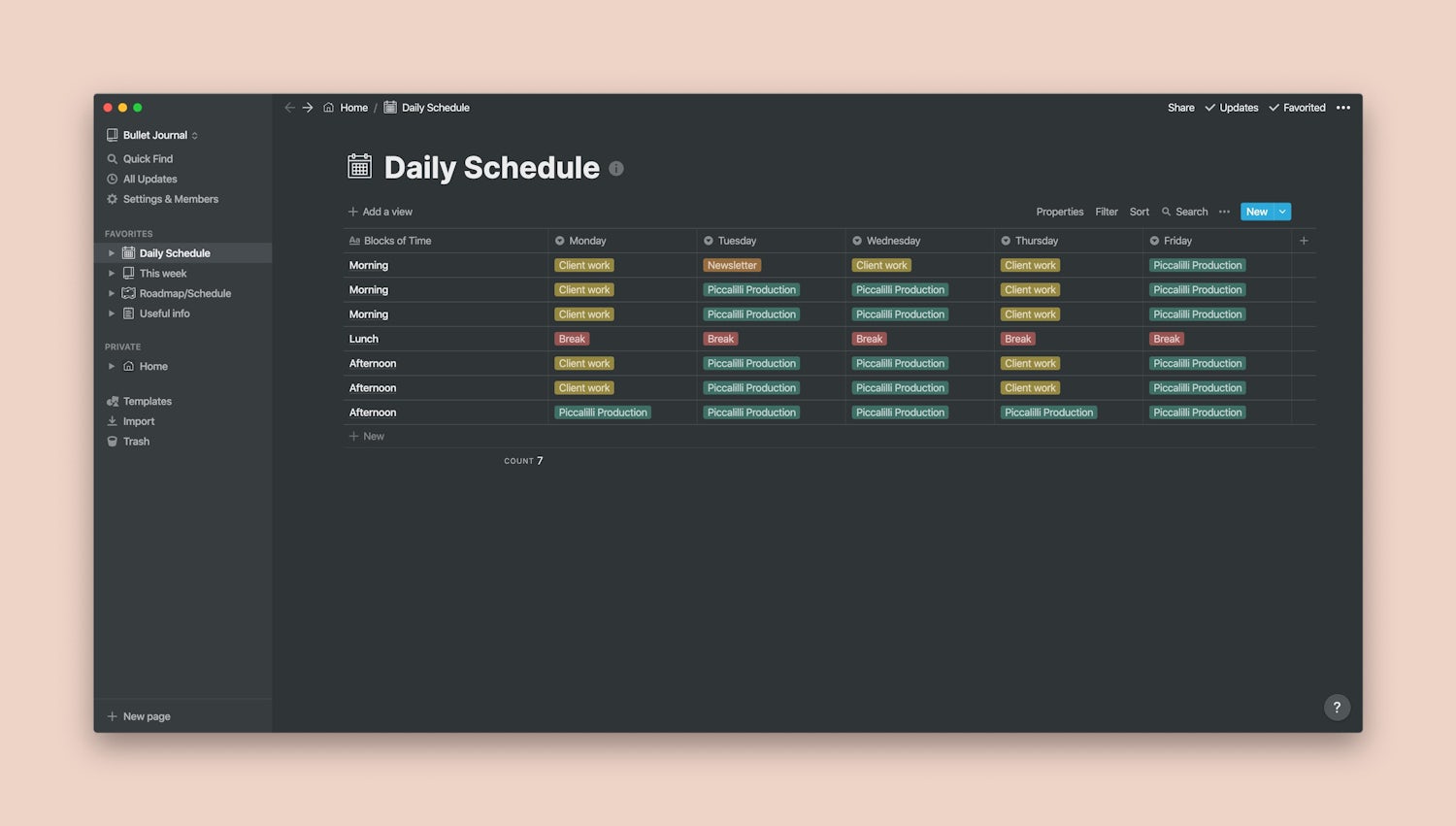

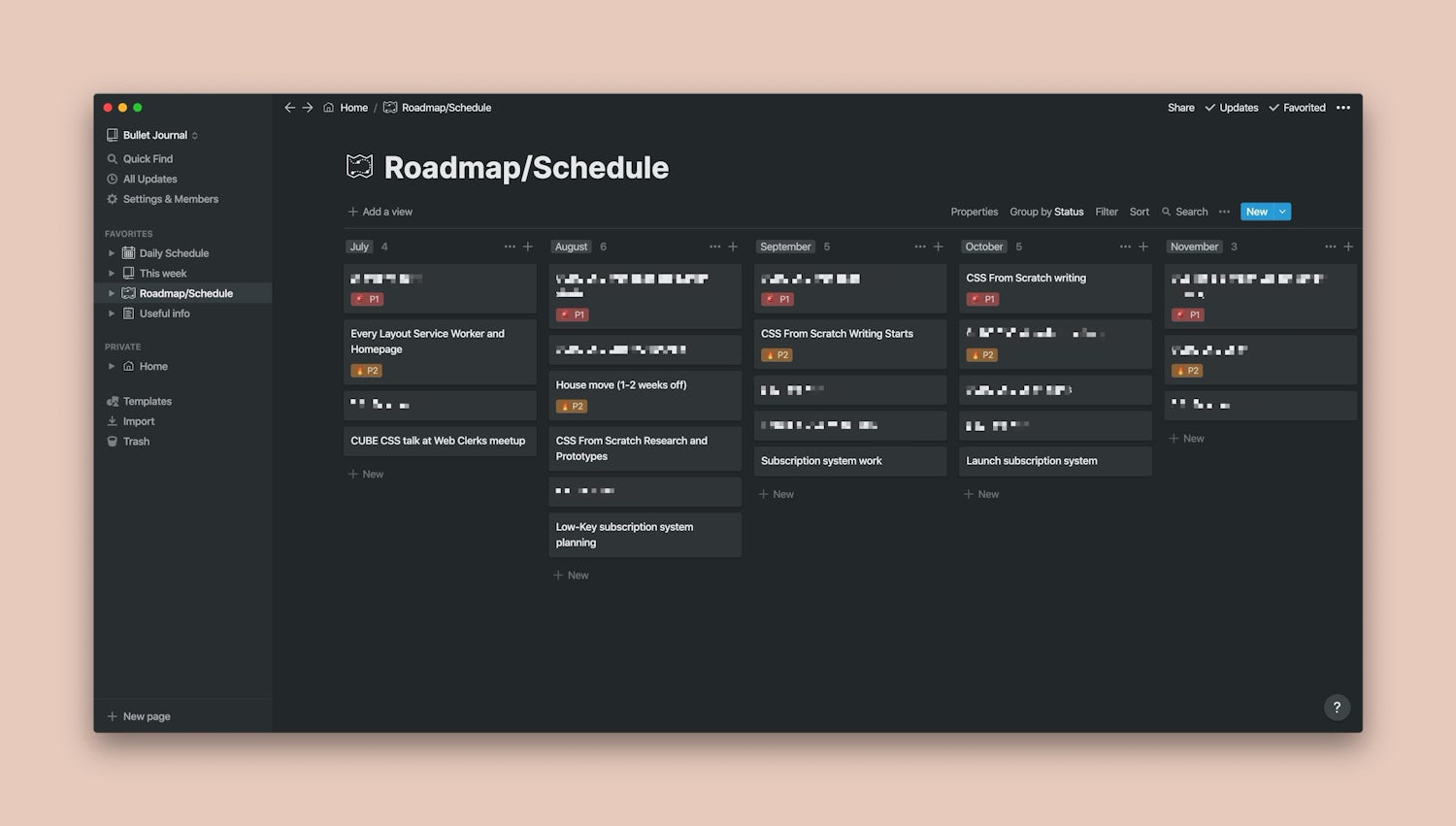

Those who know me well, know that I organise everything to within an inch of its life. I do all of this organising in Notion and Things. Notion is the main hub of planning, scheduling and client communications (yep, you read that right). Things is what I use to manage my tasks. I did previously do this in Notion and before that, in a bullet journal, but now, Notion is the main bullet journal and Things does its job well for me.

I prioritise my tasks with 🚨 P1 and 🔥 P2, with the rest being optional for the day.

I’m not going to tell you how to plan and organise in this post. Maybe I will go into more detail if there’s an appetite for it, but the main theme is however you want to do it, just do it. Being disorganised, when you are your own boss will surely be a disaster and even having a notepad with a todo list on it is better than nothing.

I strongly recommend that you schedule what you are working on each day in advance. I’d still give yourself a bit of flexibility because you might not be in the mood to say, do some creative work once you wake up, but planning time in advance is really helpful not just to keep track of where your projects are, but also where your next availability is, which segues us nicely to the next section.

I break the morning and afternoon into 3 slots then book my time around those.

Roadmapping your time like this is super helpful to get an idea of what’s coming up and where you can squeeze clients in.

Don’t wait to find workpermalink

Now that you are super organised, you’ll know on your schedule where the gaps are. Don’t wait to fill them: start putting feelers out for projects immediately.

If I see a gap that I want to fill come up, I send out a tweet along the lines of this:

I’ve got a bit of availability coming up, so if you need some design or front-end development work, give me a shout and we’ll get it booked in!

I keep the timing vague because all I’m doing here is gathering a couple of leads. The tweets will often lead to nothing, but it does plant the idea that you have availability in people’s heads. If someone knows of work coming up a month later, they might think: “Oh, I saw Andy had availability coming up. I should recommend them”.

Being organised with this stuff gives you flexibility for this sort of chance recommendation to happen. If you wait right until the last minute to land work, there’s a good chance that your tweet/instagram/mailshot will land nothing and you will go into panic mode (unless you have a large buffer). This is often when you’ll snatch at a project and land a nightmare client.

I won’t tell you where to find work because that varies a lot, but my advice is to network in your industry and get to know people. Building a reputation is so important because people will recommend you to potential new clients if you’re a pleasure to work with and do a good job. I get most of my client work via a recommendation from someone else now.

That doesn’t fix the problem of how to land that first project, though. I think for that, tweeting that you’re going freelance (I’ll always RT if you send me the tweet) and alerting people in your network will probably get you that first freelance job.

Contracts, insurance and depositspermalink

Contracts and insurance are so important. Insurance especially so if you’re not going to incorporate as a company (still get insurance if you do). I have insurance with With Jack, who are fantastic. Basically, if I mess up, I won’t get ruined because I have insurance. If you are writing code for clients, please insure yourself, because at some point, you probably will mess up.

Contracts achieve two things in my experience. They build trust between client and vendor (that’s you). A contract could be really simple, like Andy Clarke’s Contract Killer. I would recommend getting something a bit more bulletproof for very large projects though. This is where I would turn to a legal professional.

Lastly, get at least 50% of your project budget up-front if you are charging a flat rate and if not, get some form of deposit. There are only a tiny handful of clients that I won’t take a deposit off, only because I trust them a lot. Normally, that deposit has to be in my bank before I even lift a finger because if the client suddenly decides they are going to be bad payers (it happens a lot unfortunately), you have a good chunk of money still. Remember when I said charge 3X what you need? You ’d be pretty thankful for that right now if it all goes pear shaped.

Incorporate or don’tpermalink

I run my freelance business as a Limited Company. I didn’t technically need to do that, but the main reason I do is liability. It also gives me flexibility. Those who have purchased content on this site (thank you) will have probably noticed that you pay my limited company, Andy Bell Design Ltd which trades as Piccalilli.

If you get good insurance (use With Jack, seriously), then running as a Sole Trader is more than fine. When I first started out in the industry, it’s what I did and it was fine. Just be aware that some corporate clients don’t like working with Sole Traders, so being a Limited Company can be useful for that too.

Get a good accountant regardless. I can’t stress enough how a good accountant is your most important expense. In fact, a good accountant will most likely pay for themselves. It’s all well and good using fancy accounting tools, but when it comes down to the nitty gritty of tax returns—especially self-assessment—a good accountant will make that process so much easier and most likely cheaper. They also very often give fantastic business advice. Please, for the love of everything, don’t try to run a Limited Company without one especially if you are VAT registered.

Make sure you get a separate bank account, too. I use Monzo business.

Get good at communicationpermalink

The last part of this post is a tip on communication. Get good at emailing. I know I run most stuff through Notion, but the same principles apply, even in there.

Short, concise communication is the best way: trust me. I’ll be extremely opinionated on this because being concise (often blunt) works very well for me. When I write an email, it’s extremely short and to the point and will very likely feature bullet points. It has to be readable in less than a minute. This means that you should probably remove pleasantries such as the infamous “I hope you are well” or worse: “I hope this email reaches you well”—written as if the email was delivered by a donkey, via a mountain range…

The reason to keep things short is that people are busy. You might feel like you are being polite, riddling a email with pleasantries, but really, you’re probably being the opposite, taking up their time. If I see a wall of text in my inbox, I’ll set it aside until I can be arsed reading it, which in a lot of cases, is never. Getting good at writing short emails is something that happens over time though, so get practicing now!

Lastly, meetings are a time-sink. I often joke that I am a professional meeting-dodger because I hate them. Granted, some things require a meeting, but most stuff can be done with written communication. I actually like to record screen-casts, which you can read up on here. Also, don’t join your client’s Slack: they aren’t paying you for 24/7 support!!

Wrapping uppermalink

It’s worth noting that this post is written by me, a CIS white guy from the UK. I couldn’t be more privileged if I tried, so take my advice with a pinch of salt.

I do hope it has been useful, though. If you are thinking of going freelance: do it. I believe in you! Going freelance was by far the best decision I ever made. I did it at a very stressful time—shortly after being made redundant—but now, it would take a hell of a lot for me to even consider working for a company again.

Take it easy and good luck if this is the start of your freelancing career 🙂